It’s a widespread myth that ska evolved from mento. Actually, ska and all that followed came from our embryonic attempts to copy imported music to fuel 1950s sound systems’ fierce rivalry. The thirst for ‘exclusive’ popular music drove our fledgling industry.

At first, records were imported and labels erased to ‘out-exclusive’ competition until it dawned on pioneers like Clement ‘Coxsone’ Dodd, Prince Buster, Duke Reid (The Trojan) and King Edwards that the same result was possible by making our own. Early recordings (Shufflebeat) imitated 1950s blues music to the extent that Roscoe Gordon, a blues legend, claimed to be the father of Jamaican music.

Coxsone’s studio band (Clue J and the Blues Blasters), featuring guitarist Ernie Ranglin, saxophonist Roland Alphanso, trumpeter Johnny Moore, Emmanuel ‘Rico’ Rodriquez, an excellent trombonist, and bandleader Cluett Johnson (double bass), dug the foundation. TheirBeeston Street Riff remains one of Jamaica’s best instrumental recordings. They backed early vocalist Theophilus Beckford whose Easy Snappin might’ve been Jamaica’s first ‘pop’ song. The cement was poured by Owen Gray and Laurel Aitken; Prince Buster’s lyrical war with Derrick Morgan; Eric ‘Monty’ Morris. Leslie Kong’s Beverley’s label gave us Bob’s first recordings (One Cup of Coffee/Judge Not, featuring ‘Deadly’ Headley Bennett’s alto sax); Jimmy Cliff (failed to impress King Edwards at audition); Toots and the Maytals; Desmond Dekker and the Aces.

Shufflebeat proved too slow for the dances. Enter ska. Tommy McCook, a jazz musician who disliked pop, insisted on sophisticated music with complex solos. Ska-ta-lites ruled, and when Don Drummond arrived, Rico Rodriquez disappeared.

ROCKSTEADY’S FORTUITOUS GENESIS

Ska lasted three years. Coxsone told me rocksteady was created from necessity when the horns men didn’t come to work. He insisted the rhythm section record regardless. Yet the first rocksteady recording I recall came from Federal Studios:

“Everybody gonna keep on movin (right now, sir)

Gonna keep on coming in

to this dance …

Gonna put on the pressure,

sounds and pressure.”

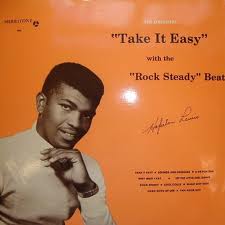

Hopeton Lewis, a Camperdown student, followed up with Take It Easy, which he often said embarrassed him whenever it played on the bus. Passengers’ natural ingenuity altered the lyrics and made a schoolboy blush.

Despite reggae’s international success, rocksteady produced the sweetest music. ‘Twas a time of perfect harmony with groups like The Heptones (named from a Heptone wine bottle found in the trash); the Paragons (legends John Holt and Bob Andy in the same group); the Tamlins (who covered ‘Baltimore’, producing my best example of local harmony); and the Melodians.

“Oh, what sweet sensation.

Lord, what strange emotion.

You got love and devotion

and I won’t forget your touch.”

Tony Brevett (Lloyd Brevett’s nephew), Brent Dowe and Trevor McNaughton created the Melodians’ remarkable catalogue. Dowe and McNaughton wrote the seminal Rivers of Babylon (1970), subsequently covered by Boney M without rewarding the authors. Boney M’s stage band included two Jamaicans who, between engagements, sang the song in the tour bus. Clandestinely, the group’s manager recorded them and gave the tape to their studio band, which arranged/backed Boney M’s cover. That became 1978’s monster hit, but when in 2006, Brent Dowe suffered a fatal heart attack while rehearsing, he died a pauper.

Allegedly slow and monotonous, rocksteady’s time soon ended. Claims to reggae’s paternity abound, but in 1968, I heard for the first time the unique Studio One sound that eventually became ‘reggae’:

“… Oh, no, oh, no, I’m not gonna let you go

now that I love no other one but you

and I always try my best to make you feel all right.

Oh, no, oh, no, I’m not gonna let you go.”

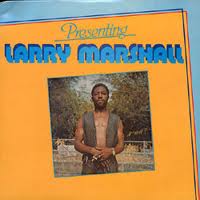

Larry Marshall and Alvin Perkins’ Nanny Goat set reggae off and running. It was exported by Marley, who joined up with the Wailers (including Peter MacIntosh; Neville ‘Bunny Wailer’ Livingston; Junior Braithwaite; Beverley Kelso and Cherry Smith) at Studio One. The first wave of ska/rocksteady exports had targeted Britain with Millie Small, Alton Ellis and Desmond Dekker. Bob expanded the market worldwide.

The Wailers spanned all three beats, recording Simmer Down for ‘Coxsone’ Dodd; Trench Town Rock, produced by Allan ‘Skill’ Cole; and ‘Duppy Conqueror’ (for Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry). Then came Chris Blackwell.Catch a Fire/Burning introduced reggae worldwide, and the Wailers – minus Bunny and Peter – were reborn with Junior Marvin, Al Anderson, Tyrone Downie, Earl ‘Wire’ Lindo, Alvin ‘Seeco’ Patterson (who secured Bob’s first audition) and the I-Threes.

Peace and love.

Gordon Robinson is an attorney-at-law. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.

You must log in to post a comment.