At the time of his death in May 1981, Bob Marley was 36 years old, the biggest star in reggae and the father of at least 11 children. He was not, however, a big seller.

For Dave Robinson, this presented an opportunity.

Two years after Marley’s passing, Chris Blackwell, the founder of Marley’s label, Island Records, brought Robinson in to run his U.K. operation. Robinson’s first assignment was to put out a compilation of Bob Marley’s hits. He took one look at the artist’s sales figures and was shocked.

Marley’s best-selling album, 1977’s Exodus, had moved only about 650,000 units in the United States and fewer than 200,000 in the United Kingdom. Those were not shabby numbers, but they weren’t in line with the artist’s profile.

“Marley was a labor of love for employees of Island Records,” says Charly Prevost, who ran Island in the United States for a time in the 1980s. “U2 and Frankie Goes to Hollywood and Robert Palmer is what paid your salary.”

Blackwell handed Robinson – the co-founder of Stiff Records, famous for rock acts like Nick Lowe and Elvis Costello – an outline of his vision for the compilation, which Blackwell says presented Marley as somewhat “militant.” “I always saw Bob as someone who had a strong kind of political feeling,” Blackwell says, “somebody who was representing the dispossessed of the world.”

Robinson balked. He’d seen the way Island had marketed Marley in the past and believed it was precisely this type of portrayal that was responsible for the mediocre numbers.

“Record companies can – just like a documentary – slant [their subjects] in whatever direction they like,” Robinson says. “If you don’t get the demographic right and sorted in your mind, you can present it just slightly off to the left or the right. I thought that was happening, and had restricted his possible market.”

Robinson believed he could sell a million copies of the greatest-hits album. To do it, however, he would have to repackage not just a collection of songs but Marley himself.

“My vision of Bob from a marketing point of view,” Robinson says, “was to sell him to the white world.”

The result of that coolly pragmatic vision was Legend: The Best of Bob Marley and the Wailers, which became one of the top-selling records of all time, far exceeding even the ambitious goals Robinson had set for it. Unlike the Backstreet Boys’ Millennium, ‘N Sync’sNo Strings Attached and many other best-selling albums in recent decades, Legend isn’t a time capsule of a passing musical fad. Selling roughly 250,000 units annually in the United States alone, it has become a rite of passage in pop-music puberty. It’s no wonder that, on July 1, Universal will release yet another deluxe reissue, this time celebrating the album’s 30th anniversary.

Few artists have hits collections that become their definitive work. But if you have one Bob Marley album, it’s probably Legend, which is one reason that members of his former backing band, The Wailers, are performing it in its entirety on the road this summer. Legend also defines its genre unlike any other album, introducing record buyers to reggae in one safe and secure package. In fact, it’s been the top-selling reggae album in the United States for eight of the past 10 years.

“It doesn’t just define a career, it defines a genre,” says David Bakula, senior vice president of analytics at Nielsen SoundScan. “I don’t think you’ve got another genre where you’ve got that one album.”

Robert Nesta Marley was born on his grandfather’s farm in the Jamaican countryside in 1945. His father, Norval Marley, was white, of British descent. He was largely absent from his son’s life, and died when Bob was 10. Two years later, Bob’s mother, Cedella Booker, an African Jamaican, moved the family to Trench Town, a poor, artistically fertile neighborhood in Kingston.

A budding musician, at age 16 Marley scored an audition with a not-yet-famous Jimmy Cliff, then a label scout.

“My first impression of him was he was a poet and he had a great sense of rhythm,” says Cliff, now 66 and on tour himself this summer. “And I think he carried that on throughout his career.”

In 1962, Cliff’s label, Beverley’s, released Marley’s first single, “Judge Not,” a ska shuffle. Soon after, Marley formed The Wailing Wailers (later shortened to the Wailers) with a core group of musicians that included Neville Livingston (aka Bunny Wailer) and Peter Tosh. All three men practiced Rastafari, a religion and way of life that emphasizes the spiritual qualities of marijuana.

“We didn’t use no drugs; we only used herb,” says Aston “Family Man” Barrett, a bass player, longtime Marley collaborator and current leader of The Wailers. “We use it for spiritual meditation and musical inspiration.”

For Island Records, the band released two albums that merged reggae with rock & roll. The initial printing for the first LP, 1973’s Catch a Fire, opened on a hinge to look like a Zippo lighter, at a time when Americans could do hard time for possessing even a single joint. Burnin’, also from 1973, featured the Marley composition “I Shot the Sheriff,” a song about police brutality, which later became a hit for Eric Clapton. On the LP’s back cover, Marley is smoking a fatty.

When Livingston and Tosh left the band, in 1974, Marley continued on as Bob Marley and The Wailers. He also became entrenched in Jamaica’s often violent political wars. In 1976, he and several members of his entourage were shot two days before he performed at the Smile Jamaica Concert, an event intended to help ease tensions ahead of an election. The gunmen were never found.

In 1980, Marley visited Cliff at a studio in Kingston. By this time, both men were internationally recognized reggae stars; Cliff had broken through with the 1972 movie The Harder They Come and its corresponding soundtrack. Though Marley had been treated for a malignant melanoma on his toe in 1977, Cliff noticed nothing out of the ordinary about his health as Marley embarked on a tour in support of his latest album, Uprising.

Al Anderson, a guitarist with Bob Marley and The Wailers, remembers the Uprising tour as “an amazing time,” with the band picking up momentum. But when the tour got to Ireland, Anderson says, Marley mentioned that he was having trouble singing and performing. “He knew he wasn’t well,” Anderson adds.

On Sept. 20, 1980, following a two-night stand at Madison Square Garden, Marley went for a jog in Central Park. He collapsed, had what appeared to be a seizure, and was rushed to a hospital. There, doctors told him that cancer had spread throughout his body. His next show would be his last.

It’s not that Bob Marley didn’t have white fans when he was alive. Caucasian college students in the United States – particularly those around Midwestern schools, including the University of Michigan, Prevost says – constituted a large percentage of his fan base. But for the compilation to meet Robinson’s lofty sales goals, those students’ parents had to buy the album, too.

Robinson had a hunch that suburban record buyers were uneasy with Marley’s image – that of a perpetually stoned, politically driven iconoclast associated with violence. So he commissioned London-based researcher Gary Trueman to conduct focus groups with white suburban record buyers in England. Trueman also met with traditional Marley fans to ensure that the label didn’t package the album in a way that would offend his core audience.

Less than a decade before violence and drugs became a selling point for gangsta rap, the suburban groups told Trueman precisely what Robinson suspected: They were put off by the way Marley was portrayed. They weren’t keen on the dope, the religion, the violent undertones or even reggae as a genre. But they loved Marley’s music.

“There was almost this sense of guilt that they hadn’t got a Bob Marley album,” Trueman says. “They couldn’t really understand why they hadn’t bought one.”

At home one night, Trueman mentioned to his wife, Sue, that many of the respondents referred to Marley as a “legend.” He said he was going to recommend the title The Legendary Bob Marley. She shot back: “No, just call it Legend: The Best of Bob Marley.”

Island employee Trevor Wyatt, known as the label’s reggae guy, gave Robinson an initial list of songs, which were played to focus groups for feedback. Robinson spent months arranging the order of the tracks. At the time, his wife was pregnant; they’d go for drives, listening to different sequences of the album on cassette. Robinson swears that his unborn son would “kick his mother to pieces” when he liked what he heard.

“The running order is so crucial,” Robinson says. “Some people like to do it chronologically, and I think that’s all rubbish. When you’re doing a greatest-hits, you have to get it to work. It has to get to the end, and you want to put it back on again.”

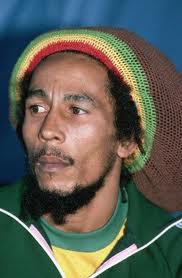

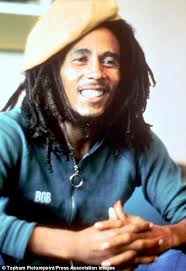

Perhaps most critically, Robinson softened Marley’s image. He chose a cover photo in which Marley appears more reflective than rebellious. He tapped Paul McCartney to make a cameo in the music video for the album’s first single, “One Love,” which portrayed Marley as a smiling family man. He even chose not to use the word “reggae” to promote the record, with a marketing campaign that included radio and television commercials – a novel and expensive idea at the time but one Robinson felt was necessary.

Released three years after Marley’s death, Legend was an immediate, unqualified hit in the U.K. In the sprawling United States, however, success didn’t come as quickly. Prevost says Island spent $50,000 on TV commercials that didn’t move the needle. But the album sold gradually and relentlessly.

SoundScan didn’t start tracking U.S. album sales until seven years after Legend‘s 1984 release, yet it’s still one of the top 10 sellers in the SoundScan era, with more than 11 million albums sold. Universal Music Group, which is now Island’s parent company, says that worldwide, more than 27 million copies of Legend have been shipped.

Despite, or perhaps because of, its success, Legend left behind it a host of problems.

The millions of dollars that the record (and other Marley albums) have brought in have sparked a tug-of-war between Marley’s musicians and the songs’ rights holders; numerous lawsuits have been filed by members of The Wailers against Island and Universal. In 2006, a justice in London’s High Court dismissed a lawsuit brought by Aston Barrett against Island seeking $113 million for royalties and songwriting credits.

“There was a lot of hard work from The Wailers band members to help produce Bob’s music that just never got credited,” says guitarist Anderson, who, like Barrett, recorded extensively with Marley and appears on Legend cuts such as “Could You Be Loved.”

(Spokesmen for Chris Blackwell and Universal didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

Meanwhile, Barrett’s and Anderson’s camps have been involved in lawsuits over the right to perform under the Wailers name, and today each musician leads a competing version of the group. Anderson’s group is called The Original Wailers, while Barrett’s band is known simply as The Wailers.

Even Legend‘s music is not without its critics.

Writing for Slate, Field Maloney called the album “a defanged and overproduced selection of Marley’s music. Listening to Legend to understand Marley is like reading Bridget Jones’s Diary to get Jane Austen.”

For their parts, Blackwell calls the album “wonderful,” Anderson says it is “likable” and Cliff is ambivalent. “I have not listened to that record, really,” Cliff says.

While it’s unfortunate that Marley didn’t live to see the success of Legend, Robinson speculates that the album might never have been made on his watch.

“Greatest-hits projects, the ones that really work, unfortunately work mainly because the people are dead,” he says. “These kinds of artists, left to their own devices, would have a different greatest-hits. A living artist will tell you that the greatest song he’s ever written is the one he’s last written.”

Marley’s son Julian has another theory: “Why do a greatest-hits album when you’re still here doing great things?”

Yet it’s hard to argue that Legend isn’t an iconic work musically. The songwriting on “No Woman, No Cry” and “Redemption Song” is so compelling that the works transcend genre – as Clapton’s success with “I Shot the Sheriff” demonstrates.

It’s also worth noting that Robinson didn’t intend that the record be comprehensive; he just wanted to get Marley’s music onto stereos worldwide. In doing so, he did something bigger: He helped make Marley’s image and message ubiquitous. Today you’ll see the artist’s face on beach towels and his lyrics on posters in countries from Russia to Chile.

And, ironically, over the past three decades, rebelliousness and violence have become a routine method of marketing pop stars. Robinson may have softened Marley’s image, but he didn’t whitewash it. Marley remains an international touchstone of rebellion, known as much for his social and cultural convictions (and his affinity for good bud) as for his musical oeuvre.

Though Legend may be the preferred dinner-party soundtrack for polite company, it also has been the gateway drug for generations of Marley aficionados. They heard something in the record and wanted more.

You must log in to post a comment.