Returning to Nigeria, 22 years after his first visit, reggae music icon, Don Carlos, recounts intimate experiences with his Nigerian fans. Nseobong Okon-Ekong reports—

Not customary with the character of entertainment star of his stature and fame, reggae music icon, Don Carlos, real name, Ervin Spencer, was alone in his hotel room in Lagos. He answered the door himself. Of course, he was familiar with the caller, Raheem Agoro, a radio presenter and promoter of reggae music who facilitated his visit to Nigeria. Carlos was the headline performer at the 18th edition of Felabration.

Carlos had only been to Nigeria once in 1996. A Nigerian friend of his, General Stano, met with him in Ghana and together they returned to Nigeria, but it was not for a performance date. It was a social visit that the reggae musician cherished and desired a repeat. Carlos has a sentimental attachment to Nigeria that was at once distant and spiritual. Of his large fan base in Africa, Nigeria is arguably where he commands the highest respect and this can be verified from the loads of fan mail coming out of Nigeria.

Performing in Nigeria was a dream come true of sorts. Finally, he had the opportunity to interact with admirers he calls brothers and sisters. The feelers from outside promised a warm reception. As he sat on the bed with a bounce, he extended his hand for a shake and urged me to sit next to him. I was the only one he did not recognize, Raheem and Azubuike were well-known to him.

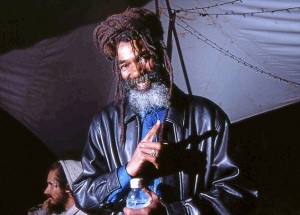

For a 62 year-old man, Carlos’ lean physique and matt of grey beard, conveyed a notion of weakness which was surprisingly countered by his quick reflexes as he bounced on the bed and motioned with flaying hands for emphasis.

It was unimaginable to witness a Carlos performance without his alter ego, Gold. Unknown to many in this part of the world, Gold had suffered a bad stroke of fate that put him out of action. Paralysed and bogged down by impaired speech, Gold’s disability is further compounded by the loss of an arm from gun shot injuries during an attack in Washington DC in 1998.

In Jamaica at the moment recuperating, chances of Gold ever performing again is slim as his movement on stage is likely to be limited. It took Carlos a long time to get over the Gold accident. Even as he is learning to cope, things are not quite the same because he was closer to Gold than his blood brother. He drew a lot of inspiration from him.

With Gold out of the way and his band not with him on this trip to Nigeria, there was a concern about how Carlos was going to cope. He quickly addressed the fears, saying it would be an honour to perform with Femi Kuti’s Positive Force Band. “I know he’s a champion and also the son of a legend too. I didn’t get to perform with his dad but I did once with Femi on Reggae Sunsplash, a long time. Femi is OK and I will do some collaboration with him,” he said. Arriving Nigeria two days before he was due to perform gave him ample chance to go over the songs he was going to showcase with the Positivie Force Band.

As much as Carlos would have loved to play with his band, he has gotten used to the free-flowing manner of their relationship. “The thing with my band is that my band we may not be together for six months. If I get a show, I call them up to meet with me. We have been together for 13 years so we know each other. The number in the band fluctuates. Sometimes, I have six men and we rotate. Normally, I have a drummer and keyboardist, guitarist. When I’m in America, I can’t utilise the band. But when I’m coming out, sometimes I make it six and one engineer. If I have an engineer on tour, I don’t have to go for sound check. When I hit the stage, everything is perfect.”

In a career that started when he was 20 years, Carlos has recorded over 25 studio albums. “I have nine for myself. Maybe like 15 or 16 with other people.”

For the Nigeria gig at Felabration, Carlos was in the company of another singer, Ina Moses, and his manager, Tabia.

Contrary to often peddled opinion, Carlos insisted that he already had a solo career and had recorded some music of his own before joining the popular reggae group, Black Uhuru. “Many people mix up that information. I recorded before joining Black Uhuru. The first time I walked into a studio was in 1965 and Black Uhuru was in 1972. I was not popular then but it is wrong to say that Black Uhuru brought me to fame. Black Uhuru came to me because of my status.” Right now, he has a loose working relationship with Black Uhuru that allows him to avoid what he describes as “controversy in the group. That’s not my style and so a lot of things make it couldn’t really happen.”

At rehearsal with the Positive Force Band at the New Afrikan Shrine, Carlos was enveloped in an air of familiarity that he could not really explain. It looked as if he was back in his birthplace in Jamaica. Was it the liberal use of marijuana or the presence of black people everywhere? He could not really place his finger on it. “A lot of people greeted and welcomed me. They were happy vibes. Just like Jamaica. Even someone came to me and I thought it was a friend called Freddy. He looked just like him. I almost asked him what he was doing there.”

Carlos had a little crossing point with Nigeria’s Fela when he performed in California. “That’s my circuit, I felt so good watching him perform but we never get to meet. He was such an influential artiste. Sometimes you are so tired and you want to go home and rest, then you hear that Fela is performing, and you just have that extra strength to watch him. I never really got the chance to be on stage with him at the same time. Fela was a very energetic entertainer and whenever he is on stage, if you feel lazy you have to move because he makes you move. That’s one thing I love about Fela, when he’s on stage, everybody is happy. So I would love to be like that. Fela was like a prophet like Bob Marley. He talked about the oppression of the people and showed you ways to go about these things. Fela was a strong man for Nigeria.”

As he was visiting Nigeria at the height of the Ebola epidemic, we wanted to know why he did not cancel his visit to avoid possible infection with the dreaded disease. “I pray to Jah because whatever I do, I talk to Jah about it and he gave me the go ahead that nothing is gonna happen. I have no fear that it will jeopardise me.”

Carlos message for his Nigerian admirers is no different from the same ideas that he canvasses all over the world. “The message to the world is love and unity because that will strengthen us, put us together, make us powerful if we really unite. One other thing, love Jah first before anything else; that’s the main message because once you know Jah, you won’t suffer.”

Although he spoke with a deliberate drawl, I had to listen well to make conventional meaning from his response in Jamaican lingo. While Carlos sees nothing bad in the dancehall slant to reggae music, he made known some of his reservations. “There is nothing wrong about the rhythm in dancehall. It’s just the lyrics and what they say in the music. You know music is pure. And music is exploration. If you are tired of one style and rhythm, you create a new style but the main thing in music is the message and lyrics. If you ever tweak a music to make people dance, say something positive about it and so that one can learn something, instead of every time singing about a girl. The dancehall rhythm is OK it’s just the way they use it. Music is really the purest form of anything.

Like many artists, Carlos would not be entangled with the rigour of choosing his best song. “There are lot of songs that I like that others don’t love. It’s not my part to choose. I really just sing the song and then the audience pick which one they like. So far, in terms of sales, ‘Passing Glance’ is one of my biggest albums. ‘Harvest Time’ is another one. ‘Raving Tonight’ was very popular in Nigeria.”

When it comes to his judgment about reception for his music in Nigeria, you cannot fault Carlos. His experience with Nigerian fans is an awesome encounter that he has no comparison. “I used to get letters from Nigeria. Suitcases of letters which I couldn’t deal with or answer at the same time. I was busy traveling. Every studio I went to in Jamaica, there was a pile of letters for me from Nigeria.” In essence these massages conveyed a measure of respect to one of the living legends of reggae music. “They wanna tell me that they love the music, that they wanna see me- lovely things.”

Seven years would pass after Carlos became a musician before he made the conscious decision to wear dreadlock. “I stopped combing my hair since 1979.”

Of all responses, his most rhetorical reaction was the abstract summation of his educational background. “I get education through liberty, day-to-day living and the knowledge Jah puts in me. I see certain things and assess movement. But normally, I just get ordinary standard education, high school but music was my thing still, education to the Rastaman is like a way to rule the mind, what they want you to be. They put you in an organisation. I’m glad I wasn’t part of them. When I was a kid, my parents thought I was lazy and immature but education wasn’t really my thing. Jah inspired everything I know. I also learn from observation.”

A master o the keyboard, Carlos tries his hands on every musical instrument. He shies away from calling himself a multi-instrumentalist; only admitting average knowledge in a rare show of humility.

You must log in to post a comment.