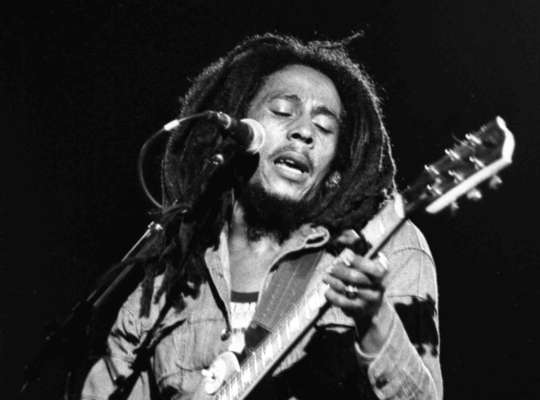

© Associated Press —-Suffering from cancer, but true to his rastafarian beliefs and refusing western medicine right till the end, reggae icon Bob Marley told his son Ziggy, “Money can’t buy life,” just moments before he died.

© Associated Press —-Suffering from cancer, but true to his rastafarian beliefs and refusing western medicine right till the end, reggae icon Bob Marley told his son Ziggy, “Money can’t buy life,” just moments before he died. “Simmer Down,” 1962

“Simmer Down,” 1962

Marley’s first hit came when he was part of the ska vocal group the Wailers, alongside his future featured bandmates, and later solo stars, Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh. Backed by the legendary Skatalites, the band took aim, peacefully, at the rude boys of Kingston, telling them to cut the crap when it came to the capital city’s prevalent violent crime, singing bubblegum pop with a Jamaican twist. Then and now, it takes guts to call out your peers, especially when they’re the ones most likely to pull a pistol.

“Concrete Jungle,” 1973

This concrete jungle isn’t one where dreams are made up. Here, Marley sings about life in a Jamaican ghetto with little to no hope for escape: “No chains around my feet/But I’m not free/I know I am bounded in captivity.” He yearns for upward mobility, but knows there’s little chance it’ll ever become his reality.

“Get Up, Stand Up,” 1973

One of the all-time great, universal protest songs, it’s worth noting that probably the best line belongs to the Wailers’ most aggressive member, Peter Tosh: “You can fool some people sometimes but you can’t fool all the people all the time.”

“I Shot the Sheriff,” 1973

After witnessing police oppression in Jamaica, which was violently divided along political lines, Marley fantasized about the justifiable killing of a corrupt cop on this single while swearing he spared the life of the innocent deputy. Given today’s tensions between law enforcement and citizens, especially the #BlackLivesMatter movement, it’s easy to see why people would identify with the sentiment. And given the causes for the anger and some of the violence that it’s led to, against citizens and police alike, it’s a reminder that there’s been too much tragedy, with little progress to show for it.

“Burnin’ and Lootin’,” 1973

Like “Sheriff,” this song reflected the frustration and anger of the people who felt suffocated by the curfews and corrupt police force in Kingston. Marley looks at the different angles of a citizen uprising, simultaneously reveling in the destruction, understanding the motivations, expressing disgust at the violence, and weeping for how far things had to fall to get to this point: “We gonna be burning and a-looting tonight (To survive, yeah)/Burning and a-looting tonight (Save your baby lives).” You might as well be reading the accounts of those who saw the shameful rioting and looting during the Ferguson, Missouri protests.

“Them Belly Full (But We Hungry),” 1974

If the people beholden to soup kitchens, food stamps, etc., ever get fed up, anyone in power would be wise to remember that, as Marley sang, “A hungry mob is a angry mob.”

“Revolution,” 1974

Marley is only getting started with the line “It takes a revolution to make a solution.” His call to arms invokes fire, blood, lightning, thunder, and brimstone, predicting that the Rastas will end up “‘pon top.” It makes the Beatles’ song of the same name seem almost apologetic in comparison.

“War,” 1976

Rastafarians regarded Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I as a living god, and this song takes its lyrics from a speech he gave before the United Nations. The first lines stay true to the speech – “Until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned” – with Marley adding, “Everywhere is war/Me say war.” While Selassie’s words and Marley’s altered, more rhythmic interpretation are focused on Africans, the message is applicable to any oppressed country, race, ethnicity, sexuality, etc.

“Crazy Baldhead,” 1976

To the dreadlocked Rastas, a “baldhead” is an outsider who, easily spotted by his lack of long coiled hair, obviously isn’t part of their spiritual movement. In this song, Marley takes aim at those who exploited their poor community: “Build your penitentiary, we build your schools” sure sounds a lot like the United States’ prevalence of for-profit prisons.

“Redemption Song,” 1980

Written after his cancer diagnosis, Marley reflects upon his impending death, spirituality, and slavery, borrowing the lines “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery/None but ourselves can free our minds” from activist Marcus Garvey. With his still-powerful voice and a gently strummed acoustic guitar, Marley put his legacy as an artist and message as an activist into just 108 words, telling all the believers to learn from their pasts, know their presents, and fight for their futures.

You must log in to post a comment.