By Todd Leopold, Larry Madowo and Jessie Yeung, CNN—

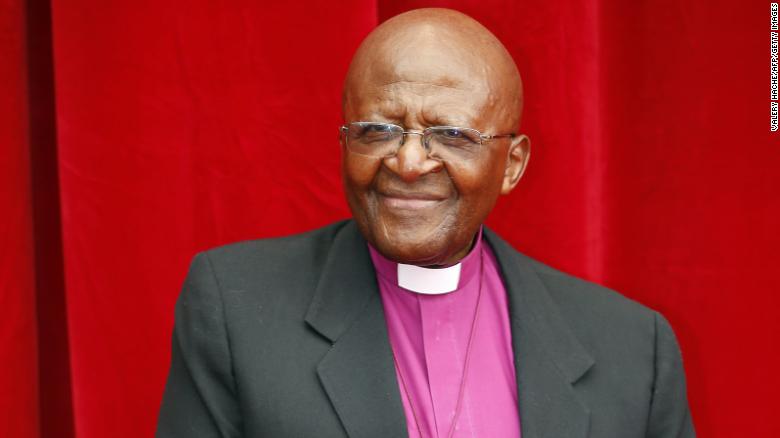

South African Archbishop and Nobel peace laureate Desmond Tutu on June 8, 2014 in Monaco.—

(CNN)

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Anglican cleric whose good humor, inspiring message and conscientious work for civil and human rights made him a revered leader during the struggle to end apartheid in his native South Africa, has died. He was 90.In a statement confirming his death on Sunday, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa expressed his condolences to Tutu’s family and friends, calling him “a patriot without equal.” ”A man of extraordinary intellect, integrity and invincibility against the forces of apartheid, he was also tender and vulnerable in his compassion for those who had suffered oppression, injustice and violence under apartheid, and oppressed and downtrodden people around the world,” Ramaphosa said. Tutu had been in ill health for years. In 2013, he underwent tests for a persistent infection, and he was admitted to hospital several times in following years.

For six decades, Tutu — known affectionately as “the Arch” — was one of the primary voices in exhorting the South African government to end apartheid, the country’s official policy of racial segregation. After apartheid ended in the early ’90s and the long-imprisoned Nelson Mandela became president of the country, Tutu was named chair of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. His civil and human rights work led to prominent honors from around the world. President Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. In 2012, Tutu was awarded a $1 million grant by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation for “his lifelong commitment to speaking truth to power.” The following year, he received the Templeton Prize for his “life-long work in advancing spiritual principles such as love and forgiveness which has helped to liberate people around the world.”

Most notably, he received the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize, following in the footsteps of his countryman, Albert Lutuli, who received the prize in 1960.The Nobel cemented Tutu’s status as an instrumental figure in South Africa, a position he gained in the wake of protests against apartheid. Despite anger about the policy within South Africa, as well as widespread global disapproval — the country was banned from the Olympics from 1964 through 1988 — the South African government quashed opposition, banning the African National Congress political party and imprisoning its leaders, including Mandela.

The path was rocky

In the 1950s, Tutu had resigned as a teacher in protest of government restrictions on education for Black children, the Bantu Education Act. He was ordained in 1960 and spent the ’60s and early ’70s alternating between London and South Africa. In 1975 he was appointed dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg and immediately used his new position to make political statements.” When we were appointed we said … ‘Well, we’ll live in Soweto,’ ” he told the Academy of Achievement, referring to the black townships of Johannesburg. “And so that — we begin always by making a political statement even without articulating it in words. “It wasn’t a plan, though from an early age he’d been inspired by Trevor Huddleston, a priest and early anti-apartheid activist who worked in a Johannesburg slum in the 1950s. By embarking on this path, he inspired thousands of his countrymen — and more around the world.” Desmond Tutu had no reason to act as he did other than his profound sense of our shared humanity in working for a world in which justice and the wellbeing of all is an expression of his ethical leadership of compassion,” wrote Episcopal priest Robert V. Taylor on CNN in 2011.Tutu believed he didn’t have a choice, even if the path was rocky.” I really would get mad with God. I would say, ‘I mean, how in the name of everything that is good can you allow this or that to happen?’ ” he told the Academy of Achievement. “But I didn’t doubt that ultimately good, right, justice would prevail.”

Tumultuous times

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born October 7, 1931, in Klerksdorp, a town in South Africa’s Transvaal province. His father was a teacher and his mother was a domestic worker, and young Tutu had plans to become a doctor, partly thanks to a boyhood bout of tuberculosis, which put him in the hospital for more than a year. He even qualified for medical school, he said. But his parents couldn’t afford the fees, so teaching beckoned.” The government was giving scholarships for people who wanted to become teachers,” he told the Academy of Achievement. “I became a teacher and I haven’t regretted that.” However, he was horrified at the state of Black South African schools, and even more horrified when the Bantu Education Act was passed in 1953 that racially segregated the nation’s education system. He resigned in protest. Not long after, the Bishop of Johannesburg agreed to accept him for the priesthood — Tutu believed it was because he was a Black man with a university education, a rarity in the 1950s — and took up his new vocation. The 1960s and 1970s were tumultuous times in South Africa. In March 1960, 69 people were killed in the Sharpeville Massacre, when South African police opened fire on a crowd of protesters. Lutuli, an ANC leader who preached non-violence, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize later that year — while banned from leaving the country. (The government finally let him go for a few days to accept his prize.)Mandela — then a firebrand leading an armed wing of the ANC — was arrested, tried and, in 1964, sentenced to life in prison. In the early ’70s, the government forced millions of Black people to settle in what were called “homelands.” Tutu spent many of these years in Great Britain, watching from afar, but finally returned for good in 1975, when he was appointed dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg. The next year he was consecrated Bishop of Lesotho. He gained renown for a May 1976 letter he wrote to the prime minister, warning of unrest. “The mood in the townships was frightening,” he told the Academy of Achievement. A month later Soweto exploded in violence. More than 600 died in the uprising.

A distinctive figure

As the government became increasingly oppressive — detaining Black people, establishing onerous laws — Tutu became increasingly outspoken. “He was one of the most hated people, particularly by White South Africa, because of the stance he took,” former Truth and Reconciliation Commission member Alex Boraine told CNN. Added Chikane, the South African Council of Churches colleague, “His moral authority (was) both his weapon and his shield, enabling him to confront his oppressors with a rare impunity.” South Africa was becoming a pariah country. Demonstrators in the United States protested corporate investment in the nation and Congress backed up the stance with the 1987 Rangel Amendment. The United Nations established a cultural boycott. Popular songs, such as the Special AKA’s “Free Nelson Mandela” and Artists United Against Apartheid’s “Sun City,” deplored the country’s politics. With his scarlet vestments, Tutu cut a distinctive figure as he preached from the bully pulpit — perhaps never more so than in his Nobel Prize speech in 1984.‘God, I don’t mind if I die now’: Desmond Tutu, in his own words After reeling off the prejudices and inequalities of the apartheid system, Tutu summed up his thoughts. “In short,” he said, “this land, richly endowed in so many ways, is sadly lacking in justice.” There were more injustices to come: assassinations, allegations of hit squads, bombings. In 1988, two years after being named Archbishop of Cape Town, becoming the first Black man to head the Anglican Church in South Africa, Tutu was arrested while taking an anti-apartheid petition to South Africa’s parliament. But the tide was turning. The next year, Tutu led a 20,000-person march in Cape Town. Also in 1989, a new president, F.W. de Klerk, started easing apartheid laws. Finally, on February 11, 1990, Mandela was released from prison after 27 years.Four years later, in 1994, Mandela would be elected president. Tutu compared being allowed to vote for the first time to “falling in love” and said — behind the birth of his first child — introducing Mandela as the country’s new president was the greatest moment of his life. “I actually said to God, I don’t mind if I die now,” he told CNN.

Controversial stances

Tutu’s work was not done, however. In 1995 Mandela appointed him chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to address the human rights violations of the apartheid years. Tutu broke down at the TRC’s first hearing in 1996.The TRC gave its report to the government in 1998. Tutu established the Desmond Tutu Peace Trust the same year. He returned to teaching, becoming a visiting professor at Emory University in Atlanta for two years and later lecturing at the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He published a handful of books, including “No Future Without Forgiveness” (1999), “God Is Not a Christian” (2011), and a children’s book, “Desmond and the Very Mean Word” (2012).He retired from public service in 2010 but remained unafraid to take controversial positions. He called for a boycott of Israel in 2014 and said that former U.S. President George W. Bush and former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair should be “made to answer” at the International Criminal Court for their actions around the Iraq war. But he was also distinguished for his sense of humor, embodied in a distinctive, giggle-like laugh. While visiting “The Daily Show” in 2004, he broke up at Jon Stewart’s jokes. And he poked fun at “On Being” interviewer Krista Tippett in 2014, chiding her for not offering him the dried mangos — his favorite — she’d brought along. Despite all the praise and fame, however, he told CNN he didn’t feel like a “great man. “”What is a great man?” he said. “I just know that I’ve had incredible, incredible opportunities. … When you stand out in a crowd, it is always only because you are being carried on the shoulders of others. “For all of his good works, he added, there may have been another reason he had so many followers. “They took me only because I have this large nose,” he said. “And I have this easy name, Tutu.”Tutu is survived by his wife of more than 60 years, Nomalizo Leah Tutu, with whom he had four children, Trevor, Theresa, Naomi and Mpho.

CNN’s Robyn Curnow contributed to this report. PAID CONTENT

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu is seen with Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II as she visited Cape Town in 1995.Hide Caption22 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu joyfully shouts “I am free! We are all free!” outside the Civic Centre in Cape Town in 1998. It was before a ceremony where he received the Freedom of the City award. In 1998, Tutu retired as the archbishop of Cape Town and became archbishop emeritus.Hide Caption23 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and the Dalai Lama attend the Nobel Peace Prize Centennial Symposium in 2001.Hide Caption24 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and other dignitaries escort the Olympic flag during the opening ceremony of the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City.Hide Caption25 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu hugs South African President Thabo Mbeki after turning over the Truth and Reconciliation Report in 2003. Tutu chaired the commission that produced the report.Hide Caption26 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu, Elmo and Oprah Winfrey appear at the Sesame Workshop’s Benefit Gala in 2004.Hide Caption27 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu wipes away tears after hearing Peter Gabriel sing “Biko” in Johannesburg in 2007. The song is about the death of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko.Hide Caption28 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu talks with Mandela at an event in Johannesburg in 2008.Hide Caption29 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesUS President Barack Obama presents Tutu with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, in 2009.Hide Caption30 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesChildren in Cape Town sing “Happy Birthday” to Tutu as he celebrates his 78th birthday in 2009.Hide Caption31 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu delivers a speech during a 2009 conference for “One Young World,” the world’s largest gathering of young leaders.Hide Caption32 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu speaks on stage during a FIFA World Cup celebration concert in 2010. South Africa was hosting the soccer tournament.Hide Caption33 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu speaks out against the South African government for its failure to grant the Dalai Lama a visa to attend Tutu’s 80th birthday celebrations in 2011.Hide Caption34 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu dances at the launch of his biography “Tutu: The Authorised Portrait” in 2011.Hide Caption35 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesObama speaks with Tutu in Cape Town following a tour of the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation Youth Centre in 2013.Hide Caption36 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu leads a service in Cape Town after Mandela’s death in 2013.Hide Caption37 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu prays during a vigil in Cape Town for the victims of a mass shooting in Orlando in 2016.Hide Caption38 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu is comforted by Dean Michael Weeder as he cries during a Mass to mark his 85th birthday in 2016.Hide Caption39 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu, accompanied by Cape Town Mayor Patricia de Lille, cuts a ribbon to unveil the “Arch for the Arch” in 2017. The architectural structure commemorates Tutu’s life and work and also represents the 14 chapters of the South African constitution.Hide Caption40 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu kisses Archie, the son of Britain’s Prince Harry and Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, in September 2019. The royal family was visiting South Africa. Hide Caption41 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and his wife, Leah, show their support for South Africa’s rugby team in this photo taken in October 2019. South Africa went on to win the Rugby World Cup.Hide Caption42 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Archbishop Desmond Tutu attends an event in Cape Town, South Africa, in April 2019.Hide Caption1 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu is seen at right with other members of the editorial staff of the Normalife, a publication produced by the students of the Pretoria Bantu Normal College in South Africa. Tutu graduated from the college with a teacher certificate in 1953.Hide Caption2 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu is seen with his mother-in-law, Johanna Shenxane, and his wife, Leah, in the Kagiso township west of Johannesburg, circa 1970. Tutu resigned as a teacher in 1957, protesting government restrictions on education for black children. He was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1961, and in 1975 he became the first black appointed Anglican dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg.

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu and his wife have four children together: Trevor, Theresa, Naomi and Mpho.

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu returns from a trip to the United Nations in April 1981. He was consecrated bishop of Lesotho in 1976. In 1978, he became the first black secretary general of the interdenominational South African Council of Churches.

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu receives the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize during the annual ceremony in Oslo, Norway. Hide Caption6 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures US President Ronald Reagan meets with Tutu in the White House Oval Office in December 1984. Tutu denounced the Reagan administration’s policy toward the South African government as “immoral” and “un-Christian.”

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu, center, leads clergymen through Johannesburg in April 1985. They were heading to police headquarters to hand a petition calling for the release of political detainees.Hide Caption8 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley attend a news conference in Los Angeles in May 1985. Tutu, an outspoken opponent of South Africa’s apartheid regime, was on a four-day fundraising tour in California.Hide Caption9 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu delivers a sermon at the Regina Mundi Church in Soweto, South Africa, in June 1985.Hide Caption10 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu mediates a dispute between police in Soweto and mothers of children who had been arrested. Hide Caption11 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu receives the Martin Luther King Jr. Award for Non-Violence while visiting Atlanta in January 1986. At left is King’s wife, Coretta Scott King. King’s daughter Christine is behind Tutu, and Tutu’s daughter Naomi is at right.Hide Caption12 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Coretta Scott King, US Vice President George H.W. Bush and Tutu sing the civil rights hymn “We Shall Overcome” during a service honoring Martin Luther King Jr. in January 1986.Hide Caption13 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesIn 1986, Tutu was elected archbishop of Cape Town, becoming the head of the Anglican Church in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Swaziland and Lesotho.Hide Caption14 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures During a 1986 news conference in Johannesburg, Tutu calls for economic sanctions against South Africa to fight the apartheid system of racial segregation. Hide Caption15 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu meets US President Bill Clinton in 1989.Hide Caption16 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and Winnie Mandela march in Cape Town to protest the continued imprisonment of anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela in February 1990. Later that day, South African President F.W. de Klerk would announce Mandela’s release.Hide Caption17 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesNelson Mandela, after being released from prison, visits Tutu in Johannesburg.Hide Caption18 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu greets Mandela at a rally, weeks before South Africa’s historic democratic election in 1994.Hide Caption19 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu casts his vote in South Africa’s first election that allowed citizens of all races to vote. “You just want to yell, dance, jump and cry all at the same time,” he said.

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu stands with Mandela after Mandela was elected president in 1994.Hide Caption21 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu is seen with Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II as she visited Cape Town in 1995.Hide Caption22 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu joyfully shouts “I am free! We are all free!” outside the Civic Centre in Cape Town in 1998. It was before a ceremony where he received the Freedom of the City award. In 1998, Tutu retired as the archbishop of Cape Town and became archbishop emeritus.Hide Caption23 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and the Dalai Lama attend the Nobel Peace Prize Centennial Symposium in 2001.Hide Caption24 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and other dignitaries escort the Olympic flag during the opening ceremony of the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City.Hide Caption25 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu hugs South African President Thabo Mbeki after turning over the Truth and Reconciliation Report in 2003. Tutu chaired the commission that produced the report.Hide Caption26 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu, Elmo and Oprah Winfrey appear at the Sesame Workshop’s Benefit Gala in 2004.Hide Caption27 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu wipes away tears after hearing Peter Gabriel sing “Biko” in Johannesburg in 2007. The song is about the death of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko. Hide Caption28 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu talks with Mandela at an event in Johannesburg in 2008.Hide Caption29 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesUS President Barack Obama presents Tutu with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, in 2009.Hide Caption30 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesChildren in Cape Town sing “Happy Birthday” to Tutu as he celebrates his 78th birthday in 2009.Hide Caption31 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu delivers a speech during a 2009 conference for “One Young World,” the world’s largest gathering of young leaders.Hide Caption32 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu speaks on stage during a FIFA World Cup celebration concert in 2010. South Africa was hosting the soccer tournament. Hide Caption33 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu speaks out against the South African government for its failure to grant the Dalai Lama a visa to attend Tutu’s 80th birthday celebrations in 2011.Hide Caption34 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu dances at the launch of his biography “Tutu: The Authorised Portrait” in 2011.Hide Caption35 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesObama speaks with Tutu in Cape Town following a tour of the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation Youth Centre in 2013.Hide Caption36 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu leads a service in Cape Town after Mandela’s death in 2013.Hide Caption37 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu prays during a vigil in Cape Town for the victims of a mass shooting in Orlando in 2016.Hide Caption38 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu is comforted by Dean Michael Weeder as he cries during a Mass to mark his 85th birthday in 2016.Hide Caption39 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu, accompanied by Cape Town Mayor Patricia de Lille, cuts a ribbon to unveil the “Arch for the Arch” in 2017. The architectural structure commemorates Tutu’s life and work and also represents the 14 chapters of the South African constitution.Hide Caption40 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu kisses Archie, the son of Britain’s Prince Harry and Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, in September 2019. The royal family was visiting South Africa.Hide Caption41 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and his wife, Leah, show their support for South Africa’s rugby team in this photo taken in October 2019. South Africa went on to win the Rugby World Cup.Hide Caption42 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesArchbishop Desmond Tutu attends an event in Cape Town, South Africa, in April 2019.Hide Caption1 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu is seen at right with other members of the editorial staff of the Normalife, a publication produced by the students of the Pretoria Bantu Normal College in South Africa. Tutu graduated from the college with a teacher certificate in 1953.Hide Caption2 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu is seen with his mother-in-law, Johanna Shenxane, and his wife, Leah, in the Kagiso township west of Johannesburg, circa 1970. Tutu resigned as a teacher in 1957, protesting government restrictions on education for black children. He was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1961, and in 1975 he became the first black appointed Anglican dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg.Hide Caption3 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and his wife have four children together: Trevor, Theresa, Naomi and Mpho.Hide Caption4 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu returns from a trip to the United Nations in April 1981. He was consecrated bishop of Lesotho in 1976. In 1978, he became the first black secretary general of the interdenominational South African Council of Churches.Hide Caption5 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu receives the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize during the annual ceremony in Oslo, Norway.Hide Caption6 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesUS President Ronald Reagan meets with Tutu in the White House Oval Office in December 1984. Tutu denounced the Reagan administration’s policy toward the South African government as “immoral” and “un-Christian.”Hide Caption7 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu, center, leads clergymen through Johannesburg in April 1985. They were heading to police headquarters to hand a petition calling for the release of political detainees.Hide Caption8 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley attend a news conference in Los Angeles in May 1985. Tutu, an outspoken opponent of South Africa’s apartheid regime, was on a four-day fundraising tour in California.Hide Caption9 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu delivers a sermon at the Regina Mundi Church in Soweto, South Africa, in June 1985.Hide Caption10 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu mediates a dispute between police in Soweto and mothers of children who had been arrested.Hide Caption11 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu receives the Martin Luther King Jr. Award for Non-Violence while visiting Atlanta in January 1986. At left is King’s wife, Coretta Scott King. King’s daughter Christine is behind Tutu, and Tutu’s daughter Naomi is at right.Hide Caption12 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesCoretta Scott King, US Vice President George H.W. Bush and Tutu sing the civil rights hymn “We Shall Overcome” during a service honoring Martin Luther King Jr. in January 1986.Hide Caption13 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesIn 1986, Tutu was elected archbishop of Cape Town, becoming the head of the Anglican Church in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Swaziland and Lesotho.Hide Caption14 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesDuring a 1986 news conference in Johannesburg, Tutu calls for economic sanctions against South Africa to fight the apartheid system of racial segregation.Hide Caption15 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu meets US President Bill Clinton in 1989.Hide Caption16 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu and Winnie Mandela march in Cape Town to protest the continued imprisonment of anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela in February 1990. Later that day, South African President F.W. de Klerk would announce Mandela’s release.Hide Caption17 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesNelson Mandela, after being released from prison, visits Tutu in Johannesburg.Hide Caption18 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu greets Mandela at a rally, weeks before South Africa’s historic democratic election in 1994.Hide Caption19 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in picturesTutu casts his vote in South Africa’s first election that allowed citizens of all races to vote. “You just want to yell, dance, jump and cry all at the same time,” he said.Hide Caption20 of 42

Photos: Desmond Tutu: A life in pictures Tutu stands with Mandela after Mandela was elected president in 1994.

It was up to the clergy to take the lead in speaking out, said Rev. Frank Chikane, the former head of the South African Council of Churches and a Tutu colleague.” We reached the stage where the church was a protector of the people, who was the voice for the people,” Chikane told CNN.

The path was rocky

In the 1950s, Tutu had resigned as a teacher in protest of government restrictions on education for Black children, the Bantu Education Act. He was ordained in 1960 and spent the ’60s and early ’70s alternating between London and South Africa. In 1975 he was appointed dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg and immediately used his new position to make political statements.” When we were appointed we said … ‘Well, we’ll live in Soweto,’ ” he told the Academy of Achievement, referring to the black townships of Johannesburg. “And so that — we begin always by making a political statement even without articulating it in words. “It wasn’t a plan, though from an early age he’d been inspired by Trevor Huddleston, a priest and early anti-apartheid activist who worked in a Johannesburg slum in the 1950s. By embarking on this path, he inspired thousands of his countrymen — and more around the world.” Desmond Tutu had no reason to act as he did other than his profound sense of our shared humanity in working for a world in which justice and the wellbeing of all is an expression of his ethical leadership of compassion,” wrote Episcopal priest Robert V. Taylor on CNN in 2011.Tutu believed he didn’t have a choice, even if the path was rocky.” I really would get mad with God. I would say, ‘I mean, how in the name of everything that is good can you allow this or that to happen?’ ” he told the Academy of Achievement. “But I didn’t doubt that ultimately good, right, justice would prevail.”

Tumultuous times

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born October 7, 1931, in Klerksdorp, a town in South Africa’s Transvaal province. His father was a teacher and his mother was a domestic worker, and young Tutu had plans to become a doctor, partly thanks to a boyhood bout of tuberculosis, which put him in the hospital for more than a year. He even qualified for medical school, he said. But his parents couldn’t afford the fees, so teaching beckoned.” The government was giving scholarships for people who wanted to become teachers,” he told the Academy of Achievement. “I became a teacher and I haven’t regretted that.” However, he was horrified at the state of Black South African schools, and even more horrified when the Bantu Education Act was passed in 1953 that racially segregated the nation’s education system. He resigned in protest. Not long after, the Bishop of Johannesburg agreed to accept him for the priesthood — Tutu believed it was because he was a Black man with a university education, a rarity in the 1950s — and took up his new vocation. The 1960s and 1970s were tumultuous times in South Africa. In March 1960, 69 people were killed in the Sharpeville Massacre, when South African police opened fire on a crowd of protesters. Lutuli, an ANC leader who preached non-violence, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize later that year — while banned from leaving the country. (The government finally let him go for a few days to accept his prize.)Mandela — then a firebrand leading an armed wing of the ANC — was arrested, tried and, in 1964, sentenced to life in prison. In the early ’70s, the government forced millions of Black people to settle in what were called “homelands.” Tutu spent many of these years in Great Britain, watching from afar, but finally returned for good in 1975, when he was appointed dean of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg. The next year he was consecrated Bishop of Lesotho. He gained renown for a May 1976 letter he wrote to the prime minister, warning of unrest. “The mood in the townships was frightening,” he told the Academy of Achievement. A month later Soweto exploded in violence. More than 600 died in the uprising.

A distinctive figure

As the government became increasingly oppressive — detaining Black people, establishing onerous laws — Tutu became increasingly outspoken. “He was one of the most hated people, particularly by White South Africa, because of the stance he took,” former Truth and Reconciliation Commission member Alex Boraine told CNN. Added Chikane, the South African Council of Churches colleague, “His moral authority (was) both his weapon and his shield, enabling him to confront his oppressors with a rare impunity.” South Africa was becoming a pariah country. Demonstrators in the United States protested corporate investment in the nation and Congress backed up the stance with the 1987 Rangel Amendment. The United Nations established a cultural boycott. Popular songs, such as the Special AKA’s “Free Nelson Mandela” and Artists United Against Apartheid’s “Sun City,” deplored the country’s politics. With his scarlet vestments, Tutu cut a distinctive figure as he preached from the bully pulpit — perhaps never more so than in his Nobel Prize speech in 1984.‘God, I don’t mind if I die now’: Desmond Tutu, in his own words After reeling off the prejudices and inequalities of the apartheid system, Tutu summed up his thoughts. “In short,” he said, “this land, richly endowed in so many ways, is sadly lacking in justice.” There were more injustices to come: assassinations, allegations of hit squads, bombings. In 1988, two years after being named Archbishop of Cape Town, becoming the first Black man to head the Anglican Church in South Africa, Tutu was arrested while taking an anti-apartheid petition to South Africa’s parliament. But the tide was turning. The next year, Tutu led a 20,000-person march in Cape Town. Also in 1989, a new president, F.W. de Klerk, started easing apartheid laws. Finally, on February 11, 1990, Mandela was released from prison after 27 years.Four years later, in 1994, Mandela would be elected president. Tutu compared being allowed to vote for the first time to “falling in love” and said — behind the birth of his first child — introducing Mandela as the country’s new president was the greatest moment of his life. “I actually said to God, I don’t mind if I die now,” he told CNN.

Controversial stances

Tutu’s work was not done, however. In 1995 Mandela appointed him chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to address the human rights violations of the apartheid years. Tutu broke down at the TRC’s first hearing in 1996.The TRC gave its report to the government in 1998. Tutu established the Desmond Tutu Peace Trust the same year. He returned to teaching, becoming a visiting professor at Emory University in Atlanta for two years and later lecturing at the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He published a handful of books, including “No Future Without Forgiveness” (1999), “God Is Not a Christian” (2011), and a children’s book, “Desmond and the Very Mean Word” (2012).He retired from public service in 2010 but remained unafraid to take controversial positions. He called for a boycott of Israel in 2014 and said that former U.S. President George W. Bush and former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair should be “made to answer” at the International Criminal Court for their actions around the Iraq war. But he was also distinguished for his sense of humor, embodied in a distinctive, giggle-like laugh. While visiting “The Daily Show” in 2004, he broke up at Jon Stewart’s jokes. And he poked fun at “On Being” interviewer Krista Tippett in 2014, chiding her for not offering him the dried mangos — his favorite — she’d brought along. Despite all the praise and fame, however, he told CNN he didn’t feel like a “great man. “”What is a great man?” he said. “I just know that I’ve had incredible, incredible opportunities. … When you stand out in a crowd, it is always only because you are being carried on the shoulders of others. “For all of his good works, he added, there may have been another reason he had so many followers. “They took me only because I have this large nose,” he said. “And I have this easy name, Tutu.”Tutu is survived by his wife of more than 60 years, Nomalizo Leah Tutu, with whom he had four children, Trevor, Theresa, Naomi and Mpho.

You must log in to post a comment.