By Ainsworth Morris/Gleaner Staff Reporter–

Photo by Ainsworth Morris—The structure which once served as a temple in the Pinnacle commune during better days.

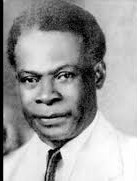

Rastafarian faithful have hailed the posthumous national honor to be bestowed on the religion’s founder, Leonard Percival Howell, as an atonement of sorts and a tectonic shift from the bitter days that characterized the movement’s infancy and its early relationship with the State decades ago.

Howell, who died 41 years ago, will this October be inducted into the Order of Distinction in the rank of Officer for pioneering the development of the Rastafari philosophy.

Although born into an Anglican family on June 16, 1898, Howell broke ties and established the first Rastafarian community with about 4,500 members and created the Pinnacle commune in the cool hills of Sligoville, St Catherine, overlooking the buzzing towns of Spanish Town and Kingston with a breath-taking view that brings peace to one’s soul.

Pinnacle grew into becoming a self-reliant community with farmers who created a sustainable culture. There were also skilled craftsmen and women who shared a faith under the motto ‘One God, One Aim, One Destiny’.

The destruction of Pinnacle, started by the colonial authorities in 1954, and the dispersal of its members, caused the Rastafarian doctrine to spread into more communities such as Waterloo and Tredegar Park in St Catherine and communities in west Kingston.

Howell died on February 25, 1981.

Frederick Findley, the sole Rastafarian still living at Howell’s stomping ground, said the honor was long in coming.

“I am happy he is being recognized now. It is a good thing for our community and he did a lot for Rastafarians and fighting for our rights and freedom,” the 68-year-old Findley told The Gleaner.

Findley recalled being introduced to Howell in the 1970s after expressing an interest in joining the Rastafarian community in his youthful days.

He would subsequently regularly take the miles-long trek from Kingston to Pinnacle to chant with Howell and other Rastafarians.

“Mi did young, and I forward up here. A never so di road [did] stay. Dem days deh was stone and bush. Dem deh was donkey cart days,” he recalled before showing The Gleaner the foundation of Howell’s house at the location.

Findley bemoaned the fact that the once-sustainable community Howell built is now left solely to him to carry its flag. The COVID-19 pandemic, he said, made things worse for the already-declining Pinnacle.

“Since the COVID, di Rasta dem hardly come here anymore. Di Rasta dem get weak! Every 16th of June, Howell’s birthday, we used to meet here and keep a little vibes, but, since COVID, that stop happening. The last time is only a couple brethren and sistren remember and come fi wi try keep the tradition alive,” he said.

The once-thriving settlement, which had hosted a library and a museum during its heyday, is now a shadow of its former glory.

Vandals and thieves have also plagued the area, stealing stones and other treasured items from Pinnacle as its landmark structures crumbled over time.

Findley wants the Government and heritage interest groups to breathe new life into Pinnacle and have it buzzing again as a tourist attraction and as a retreat for Rastafarians to meet and worship.

Perhaps the darkest period for Rastafarians in the island was between Thursday, April 11 and Friday, April 12, 1963, when bloody violence flared up in Coral Gardens, then a farming community nearly 10 miles to the east of Montego Bay, St James.

It resulted in the death of eight persons and injuries to hundreds, and severe destruction of a Rastafarian camp by members of the security forces, who were accused of human and constitutional rights violations.

In April 2017, Prime Minister Andrew Holness apologized for the State’s role in the Coral Gardens Massacre and promised compensation to victims and families of the deceased.

“[It] was wrong and should never be repeated,” the prime minister said about the 1963 Good Friday attack – later dubbed Bad Friday.

“The victims of the Coral Gardens Massacre suffered an unimaginable atrocity at the hands of the State. Though decades late, the apology given by the PM and the measures announced to compensate the survivors and their families were a welcome first step,” former Jamaicans for Justice Executive Director Rodje Malcolm later said.

Nigel Jones, a Rastafarian living meters away from Pinnacle, was elated when it was revealed on Independence Day a week ago that Howell would be accorded the national honor.

“Mi nuh know him personally, but mi have whole heap a history on him. He’s a man weh take up certain tradition and thing, so him deserve it, y’know. Him defend certain rights fi black people and African heritage,” Jones said.

“A lot of it is meaningful to me, even the brutality with police, and we see it a manifest today same.”

You must log in to post a comment.