By Vinette K. Pryce—

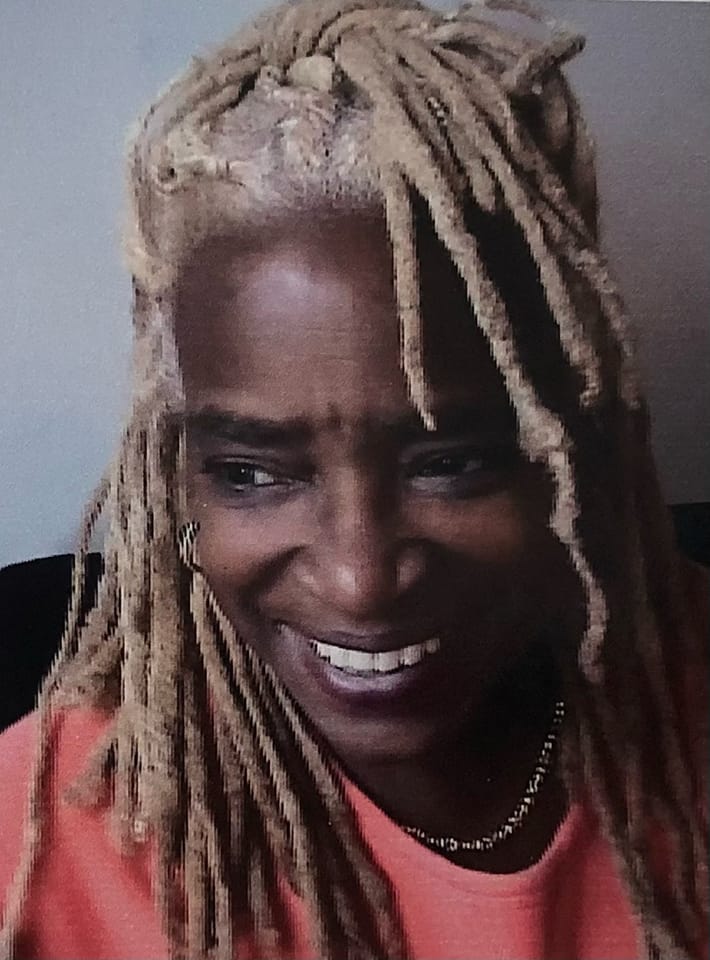

The late Janie Washington of Harlem. Photo by Vinette K. Pryce—

“In the jungle, the mighty jungle, the lion sleeps tonight…” South African, Solomon Linda in 1939.

This pulsating chorus to an infectious song awakened the sensibilities of a clueless, global audience seven decades ago when the song topped the charts in 16 countries. Credited with informing music lovers about Africa, it was first recorded in the language of South Africa’s Zulu people as “Wimoweh.”

It’s musical messaging now resonates with relevance to a legacy now being reflected following the demise of Janie Washington, a Harlem, feminist, whose roar seemed louder than most “cats in the radio kingdom.

That reference from a shocked associate tempered sadness of the passing of the longtime executive who lost her battle to terminal cancer and also aligns with similar sentiments from colleagues who knew her at Inner City Broadcasting Corporation during the heydays of radio stations WBLS-FM and WLIB-AM.

Washington’s two daughters, Kim and Jordan informed yours truly that on Dec. 6, “our mother took her last breath.”

The disarming news almost disarmed any perspective of comprehension. They sounded calm, collected and cool relating the ancestral passage of their mother’s transition.

That’s how Washington would have wanted it. She was proud, practical, private, a no fuss direct individual.

Although difficult to process, the tragic news of my 78-year-old friend was bolstered by a sensible tone the off-springs implemented in order to decipher details of the unsuspecting proceeding.

They explained that their beloved matriarch is no longer in pain.

Washington’s domain was radio. From Detroit to New York, her dominance of the landscape translated as a force for ICBC, the Percy Sutton entities and sole Black-programmers of urban music and information.

Caribbean radio listeners might have first encountered the vice president of promotions when she toiled to establish A Circle of Sisters, an annual Kwanzaa bazaar at the Jacob Javits Convention Center or at any pre-Labor Day Concert behind the Brooklyn Museum. Some might have experienced her tenacity when as general manager of WLIB-AM she selected a winning cadre of on-air personalities, helped to decide the Caribbean, music playlists, and finalized a music director compatible with the listening audience. The plethora of affiliations she was associated included the Caribbean Music Awards at the Apollo Theater, hurricane relief on many islands and a long list of remote broadcasts.

She was an advocate for KC, a soca bandleader whose hairstyle was reminiscent of James Brown, the avowed Soul Brother Number One and self-described ‘hardest working man in show business.”

Trinidad & Tobago’s “hardest working man in soca music” often performed at Washington’s behest. She often assigned KC to represent the two radio stations at the annual African American Day Parade in Harlem.

Affectionately recalled by generations of music lovers who admired her unrivaled execution of Colin Lucas’ “Dollar Wine,” the petite administrator often enjoyed dancing to music of every genre.

When then soca icon Blue Boy implored fans to “Get Something & Wave,” Washington provided plenty of WLIB initialed towels to both soak up the sweat and brandish in the air.

Haiti’s zouk was also on her radar. She managed Phantom, a band headed by King Kino. She was instrumental in booking gigs at SOB’s, the Limelight Club and aided in elevating their platform to parade along Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway.

And with Fritz Martial, the station’s ombudsman she was able to dispense news about the revolutionary progression of the Caribbean, creole nation.

At the inauguration of President Bertrand Aristide, Washington effected a broadcast from the nation; she also accompanied police brutality victim Abner Louima to Port-au-Prince when he returned home following hospitalization from reported a vicious assault from members of the NYPD.

Washington’s equal opportunity approach to music diversified listenership and when Motown Records promoted a newly-signed family group dubbed The Boys, Washington headed the promotion team slated for Dakar, Senegal.

The entourage also comprised rhythm & blues singer Vesta Williams. And while the cultural connection spotlighted a concert in the African capital, Washington ensured a tour of the Gorre Island slave dungeon that enlightened the predominant American group of the atrocities caused by colonialism.

In Ghana, Washington promoted jazz at a similar slave encampment festival in Cape Coast. She did the same in Aruba at their Aruba Jazz festival.

Add Brazil’s carnival to a list of destinations Washington frequented in order to bridge the void other radio stations defaulted.

Washington invested in audiences whose spoken language incorporated French, creole, Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish and English.

“There is no one that helped more in advancing Jamaica Carnival other than Janie Washington,” Charles Simpson recalled.

As the inaugural producer of the island’s calypso revelry at Oceana Hotel, in Kingston, he lamented Washington’s passing but reminisced her relentless effort to unite Caribbean diasporans and the immigrant community.

Trinidad & Tobago’s Jennifer Joseph said “Janie took bacchanal to Barbados during Crop Over.”

She was the adhesive that kept audiences attuned to WLIB radio.

More often than not she was accompanied by her daughters, particularly, the youngest Jordan, an early flyer.

“We will not grieve for Janie, she wouldn’t want that,” Joseph said, “it is cadoument time, we will toast her with Mount Gay Rum, that’s what she liked.”

You must log in to post a comment.