By Deon Brown—-

New York:

In the Caribbean and around the world, Jamaican music continues to be celebrated for its sound and its sweetness, and the principled activist spirit of reggae.

But even as the appeal of reggae is being acknowledged, there is some quiet soul-searching taking place with serious reggae lovers asking, has reggae lost its spirit?

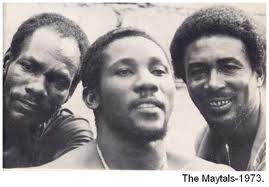

The music’s global impact is not in question. What is in doubt is its mission and message. “Reggae got soul,” Toots Hibbert sang in the heyday of consciousness music back in the ’70s.

But almost four decades later, really, has reggae lost its soul? The times, after all, are a changing.

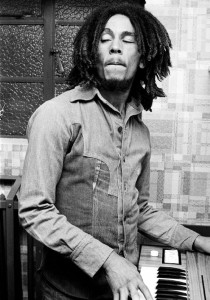

“Reggae has lost that identity and richness it had when it was a spiritual and political force,” opines Vivien Goldman, a long-time music journalist who has written extensively on world music and recently taught a popular course on Bob Marley and Jamaican music at New York University’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, where she is an adjunct professor.

“The spirit of reggae has moved on. The impact of reggae on the world is more forceful than reggae itself,” she adds.

She notes that while there are wonderful individual voices like Etana and Tarrus Riley coming out of Jamaica, there is no big front-running artiste spearheading the identity of Jamaican music in much the same way as Bob Marley did.

ARTFUL MESSAGE MISSING

Shaggy, Sean Kingston and other recent acts may have had some hits but their performances are more akin to reggae’s descendant, dancehall, which has the same audacity and certainly the entertainment value but not the depth, politics and artful message of reggae.

One could hear the rebellion in reggae, its righteous fury, raging against injustice and oppression. On the other hand, dancehall is a rebel without a cause.

“Jamaica has to continue being Jamaica,” Goldman adds.

“One of the reasons for reggae’s impact in the mid ’70s was the sound, not only the lyrics and the militant expression but the actual sound. People like King Tubby, Lee Perry and the other great dub masters.”

For the generation shaped by the authentic roots rhythm of reggae whose session musicians captured the flavour, texture, the folk bearings and the intrinsic rhythmic movement of the Jamaican people, something, they believed, went missing when the music went digital.

Reggae, arguably, may have lost its substance but not its sonic appeal. Today, a new generation stands as the inheritors of the Jamaican sound. It is on the lips and in the ears of everyone, in multiple languages. It has seeded other musical forms – in the barrios of Puerto Rico, the Spanish neighbourhoods in Latin America and the United States, the favelas (urban shanty towns) in Brazil, and numerous African cities and towns. Hip hop, raga, rave, punk – all pay homage to reggae.

The incredible audio dynamic of Jamaican music is to be found especially in reggaeton.

In this Spanish-Jamaican hybrid, one hears the thrill, beat, intensity and ripped off identity of reggae.

Reggaeton’s artists, including the rising stars, producing duo Wisn and Yandel are reggae’s godchildren.

“Jamaica is a far more influential culture than it realises sometimes,” Goldman observes.

ALLURE FADING

But while its sound remains vibrant, what critics bemoan is the loss of what made reggae, reggae.

Part of reggae’s allure was its message of unity, and its own ability to build bridges, connecting the various strands of the black diaspora.

Reggae held within it, an inclusive tissue to people of all cultures, colour, creed and consciousness. It still does. What’s lost in today’s music is its transformative power.

Consider what reggae meant to the liberation struggle in Southern Africa in the 1970s through to the early 1990s.

The potency of Jamaican protest songs fuelled the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa and the resistance fights in Angola, Namibia, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and Mozambique.

So many reggae songs were banned by the government in Pretoria because, quite simply, it frightened them and stirred up the black masses, shoring up their endurance, and giving credence to their call for justice, equality, empowerment and the acknowledgement of their humanity.

Reggae music is identity music.James Mange, a South African reggae musician and a one-time activist of the African National Congress (ANC), tells a riveting story of what reggae meant to him and other oppressed South Africans during the apartheid years.

INSPIRED FREEDOM FIGHTERS

Speaking at a Jamaica 50 forum hosted by the Jamaican High Commission in South Africa in February 2012, Mange said the compelling lyrics of reggae kept the freedom fighters alive, inspired them and allowed them to think through strategies.

Mange was first placed on death row for his resistance activities before his sentence was commuted to a 20-year imprisonment following an international campaign. He was sent to Robbin Island where he spent some 14 years.

Reggae, he said, lived in his head, and preserved his sanity.

“Reggae was the hammer that broke the fear,” he told the audience.

As he sat in solitary confinement, he kept hearing the song, 1865: 96 Degrees in the Shade by the Jamaican reggae group, Third World. The song, released in 1977 is about the 1865 Morant Bay Rebellion which resulted in the hanging of National Heroes, Paul Bogle and George William Gordon. This was music and lyrics he could identify with.

Mange sang so many reggae tunes from his cell that even the prison guards would come to him requesting more songs from the prisoner they dubbed ‘Bob Marley’.

In a recent documentary on his life, James Mange spoke even more eloquently of reggae’s role in the African liberation struggle in the 1970s.

The black citizenry had been humbled by the 1960 Sharpville massacre when police killed scores of demonstrators. The African National Congress leadership had been crippled as many of them were imprisoned or forced into political exile. The 1970s were mostly politically dormant and then reggae with its resistance motif crossed the oceans, finding its way in hidden stores and on secreted tapes, and into their hearts.

“When the reggae wave hit the country a lot of people got energised,” Mange recalled.

What it must have meant to South Africans to hear Jamaican artists singing passionately about Stephen Biko, Nelson Mandela, the oppressed masses in Soweto and other townships, and an end to their victimisation.

You must log in to post a comment.